CAZypedia needs your help! We have many unassigned GH, PL, CE, AA, GT, and CBM pages in need of Authors and Responsible Curators.

Scientists at all career stages, including students, are welcome to contribute to CAZypedia. Read more here, and in the 10th anniversary article in Glycobiology.

New to the CAZy classification? Read this first.

*

Consider attending the 15th Carbohydrate Bioengineering Meeting in Ghent, 5-8 May 2024.

Difference between revisions of "Auxiliary Activity Family 3"

m |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- RESPONSIBLE CURATORS: Please replace the {{UnderConstruction}} tag below with {{CuratorApproved}} when the page is ready for wider public consumption --> | <!-- RESPONSIBLE CURATORS: Please replace the {{UnderConstruction}} tag below with {{CuratorApproved}} when the page is ready for wider public consumption --> | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{CuratorApproved}} |

* [[Author]]: ^^^Roland Ludwig^^^ and ^^^Daniel Kracher^^^ | * [[Author]]: ^^^Roland Ludwig^^^ and ^^^Daniel Kracher^^^ | ||

* [[Responsible Curator]]: ^^^Roland Ludwig^^^ | * [[Responsible Curator]]: ^^^Roland Ludwig^^^ | ||

Revision as of 06:08, 4 May 2018

This page has been approved by the Responsible Curator as essentially complete. CAZypedia is a living document, so further improvement of this page is still possible. If you would like to suggest an addition or correction, please contact the page's Responsible Curator directly by e-mail.

- Author: ^^^Roland Ludwig^^^ and ^^^Daniel Kracher^^^

- Responsible Curator: ^^^Roland Ludwig^^^

| Auxiliary Activity Family AA3 | |

| Clan | AA3 |

| Mechanism | FAD-dependent substrate oxidation |

| Active site residues | known |

| CAZy DB link | |

| http://www.cazy.org/AA3.html | |

General properties and substrate specificities

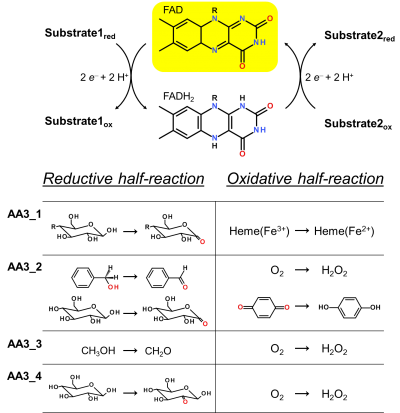

Enzymes of the CAZy family AA3 are widespread and catalyse the oxidation of alcohols or carbohydrates with the concomitant formation of hydrogen peroxide or hydroquinones [1]. AA3 enzymes are most abundant in wood-degrading fungi where they typically display a high multigenicity [2]. The main function of fungal AA3 enzymes is the stimulation of lignocellulose degradation in cooperation with other AA-enzymes such as peroxidases (AA2) [3, 4, 5] or lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (AA9) [6, 7, 8, 9]. In yeast, AA3 enzymes are involved in the catabolism of alcohols [10], and some AA3 genes identified in insects are thought to be relevant for immunity and development [11, 12]. Recently, a bacterial AA3 enzyme with unknown biological function was isolated and characterized [13]. The functionally diverse enzymes of family AA3 all belong to the structurally related glucose-methanol-choline (GMC) family of oxidoreductases and require a flavin-adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor for catalytic activity. Based on their sequences members of the AA3 family were divided into four subfamilies in the CAZy database (Figure 1). Family AA3_1 contains the flavodehydrogenase domain of cellobiose dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.99.18), family AA3_2 includes aryl alcohol oxidase (EC 1.1.3.7), glucose oxidase (EC 1.1.3.4), glucose dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.5.9) and pyranose dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.99.29), family AA3_3 consists of alcohol (methanol) oxidases (EC 1.1.3.13) and family AA3_4 comprises pyranose oxidoreductases (EC 1.1.3.10).

Subfamily AA3_1: Cellobiose dehydrogenase

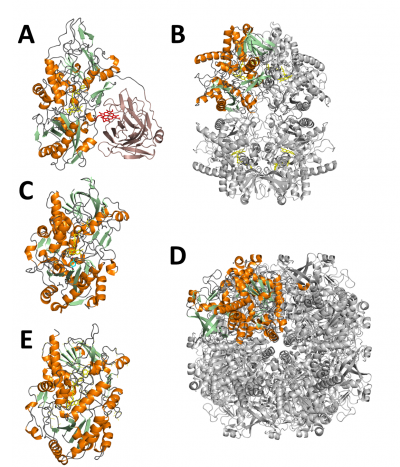

Cellobiose dehydrogenases (CDHs) are extracellular flavocytochromes that were first described in 1974 [14]. CDHs are exclusively found in wood-degrading and phytopathogenic fungi belonging to the phyla Basidiomycota (Class-I CDHs) and Ascomycota (Class-II and -III CDHs) [15]. They oxidize a wide variety of lignocellulose-derived saccharides to their corresponding sugar lactones. CDHs show a high preference for soluble, β-(1,4)-interlinked saccharides and scarcely oxidize monosaccharides. A common feature of all CDHs is their complex bipartite structure, which comprises a C-terminal cytochrome-binding domain (CYT) and a larger, catalytic flavodehydrogenase (DH) domain encoded within a single polypeptide chain [16] (Figure 2A). Both domains are connected by a flexible linker which typically comprises 15 – 30 amino acids. An important in vivo function of CDH is the reduction and activation of family AA9 lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases via its heme b domain [17, 18, 19]. Recently, the holoenzyme structures of Neurospora crassa CDH (pdb: 4QI7) and Myriococcum thermophilum CDH (pdb: 4QI6) were reported. Two structures of N. crassa CDH showed an “open-state” conformation in which DH and CYT were spatially separated, whereas a structure of M. thermophilum CDH showed a “closed-state” conformation in which the propionate arm of the cytochrome domain interacted with the catalytic centre in DH [18]. Analysis by small angle scattering also suggested a number of possible intermediate conformers that exist in solution [18, 20]. While the closed-state allows interdomain electron transfer from DH to CYT, reduction of electron acceptors (e.g. AA9 enzymes) might occur in the open-state, in which the heme cofactor is fully accessible.

Subfamily AA3_2

Aryl alcohol oxidase/dehydrogenase

Aryl alcohol oxidoreductases (AAO) are secreted by basidiomycete fungi and proposed to play a crucial role in lignin degradation. The X-ray crystal structure of the most widely studied AAO from Pleurotus eryngii (pdb: 3FIM) showed a non-covalently bound FAD cofactor in the active-site [21] (Figure 2C). Access to the active site is restricted by three aromatic residues, which interact with both the alcohol substrate and oxygen. The substrate scope of AAO includes secreted benzyl alcohols from the secondary metabolism (e.g. veratryl alcohol), or related alcohols that accumulate during lignin degradation [4]. During the reductive half-reaction, the primary alcohol of the substrate is two-electron oxidized to form the corresponding aldehyde. In addition, aromatic aldehydes can undergo further oxidation yielding the corresponding acids. The concomitantly formed hydrogen peroxide is considered essential for the activity of lignin degrading peroxidases. Recently, aryl-alcohol quinone oxidoreductases (AAQO) with a high sequence identity to Pleurotus eryngii AAO were identified in the genome of the basidiomycete Pycnoporus cinnabarinus [22]. While these enzymes showed a substrate spectrum similar to known AAOs, oxygen reduction was insignificant or very low relative to other characterised AAOs. However, reoxidation of FADH2 was very efficient with benzoquinone or phenoxy-radicals, which are formed by fungal laccases, suggesting a different functional role of AAQOs.

Glucose oxidase and glucose dehydrogenase

Glucose oxidases (GOX) (Figure 2D) and glucose dehydrogenases (GDH) catalyse the regioselective oxidation of β-D-glucose to D-glucono-1,5-lactone. Both GOX and GDH are structurally related, including a set of conserved active site residues for the binding of glucose. Therefore, a discrimination of these genes based on their sequences is difficult [2]. Glucose oxidases typically occur as homodimers whereas GDHs occur as monomers or dimers. The first crystal structure of GOX from Aspergillus niger was resolved in 1993 (pdb: 1GAL [23]). A highly conserved arrangement of active-site residues, which form hydrogen bonds to all five hydroxyl groups of β-D-glucose, is responsible for the particularly high specificity towards Dglucose. The first crystal structure of GDH from Aspergillus flavus was reported in 2013, showing a slightly less conserved active site and fewer interactions with glucose (pdb: 4YNT [24]). This may also explain the promiscuous reaction of GDH with β-D-xylose, which is not observed for GOX. Both enzymes show different cosubstrate specificities. Glucose oxidases reduce atmospheric oxygen to hydrogen peroxide in their oxidative half-reaction. Proposed native functions of the enzyme are closely related to its peroxide-producing abilities and include the preservation of honey, microbial defence as well as the support of H2O2-dependent ligninases in wood degrading fungi [25]. GDHs interact very slowly with oxygen and prefer electron acceptors like quinones or phenoxy-radicals. The detailed physiological role of GDH remains elusive, but has been previously linked to the neutralization of plant laccase activity by fungi during plant infection [26].

Pyranose dehydrogenase

Pyranose dehydrogenase (PDH) is a secretory protein found in a limited number of litter degrading fungi belonging to the families Agaricaceae and Lycoperdaceae [27]. While the overall sequential and structural similarities to other GMC-oxidoreductases are high, the enzyme differs in terms of its catalytic properties and contains a covalently linked FAD, which is not observed in other AA3_2 enzymes. PDHs are characterised by a broad substrate spectrum, which includes a number of monosaccharides (L-arabinose, D-glucose, and D-galactose, D-xylose) as well as some oligo- or polysaccharides. PDHs catalyse the C1, C2, or C3 oxidation of the sugar substrate, or introduce di-oxidations at C2/C3 or C3/C4, resulting in the formation of aldonolactones (C1 oxidation) or (di)ketosugars. The first crystal structure of the enzyme was resolved in 2013 (pdb: 4H7U) and showed an open active site conformation, which in part may also explain its high substrate promiscuity [28]. The electron acceptor specificity is similar to those of other sugar dehydrogenases and includes quinones and phenoxy radicals.

Subfamily AA3_3: Alcohol oxidase

Alcohol- or methanol oxidases (AOX) (Figure 2D) are intra- or extracellular enzymes found in yeasts and fungi. In methylotrophic yeasts, such as Pichia pastoris, AOX is a catabolic enzyme essential for the utilization of methanol. AOX catalyses the selective oxidation of primary alcohols at CH-OH, yielding the corresponding carbonyl compounds [29]. The enzyme accepts both saturated and unsaturated aliphatic alcohols with a chain length from C1 to C8, but shows a strong discrimination against secondary alcohols. To date, two structures of AOX from P. pastoris were resolved in 2016; One based on X-ray diffraction (pdb: 5HSA [30]), the other on cyro-electron microscopy (pdb: 5I68 [31]). AOX are homo-octameric enzymes located in the peroxisomal matrix [29]. Each subunit contains a covalently bound FAD-molecule modified with an arabinyl chain. In P. pastoris, the degree of the FAD arabinylation depends on the alcohol concentration in the medium and is thought to modify the reactivity with methanol. Considerably less is known about fungal AOX, which have been found in wood-degrading or phytopathogenic fungi from the phylum Basidiomycota. Similarly to AOX from yeast, they showed an octameric architecture and displayed the highest catalytic efficiencies for methanol. The fungal AOX from Gloeophyllum trabeum was identified as extracellular protein despite the lack of a dedicated secretion signal peptide [32]. The native function of fungal AOX could therefore be related to its peroxide production, which, similar to other AA3_2 enzymes, can potentially stimulate fungal attack on lignocellulose by supplying H2O2 to peroxidases. AOX secreted by the phytopathogenic basidiomycete Moniliophthora perniciosa, the causative agent of Witches’ broom disease in the cocoa tree, is thought to play a role in the utilization of methanol derived from pectin demethylation [33].

Subfamily AA3_4: Pyranose oxidase

Pyranose oxidases (POX) (Figure 2B) are widespread in lignocellulose degrading fungi and catalyse the C2-oxidation of monosaccharides. POX is the most distantly related member of the AA3 family and does not show the strict conservation of structural motifs found within the AA3 family. Unlike other AA3 enzymes, POXs are associated with membrane-bound vesicles and other membrane structures in the periplasmic space of the fungal hyphae. The first crystal structure of POX was reported in 2004 (Trametes multicolor, pdb: 1TT0 [34]). The enzyme is a homo-tetramer with each of the subunits carrying a covalently bound FAD molecule. A distinct “head domain” on each of the subdomains is thought to be involved in oligomerization or in interactions with cell wall-polysaccharides [34]. Access to the active site of the enzyme is modulated by a flexible active-site loop, which hinders entrance of oligosaccharides. Substrate channels lead from the polypeptide surface to an internal large cavity formed by the four subunits. The preferred substrate of POX is either α- or β-D-glucose, but also D-galactose, D-xylose, or D-glucono-1,5-lactone are converted [35]. Substrates are oxidized at the C2 position to yield 2-ketoaldoses as products. In the oxidative half-reaction, the FADH2 is regenerated by reduction of O2 to H2O2. The reduction of oxygen by POX proceeds through a C4a-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate, which is characteristic for FAD-dependent monooxygenases but is untypical for sugar oxidases [36]. Apart from oxygen, POX can also utilize alternative electron acceptors including a number of (substituted) quinones and (complexed) metal ions. Of note, catalytic efficiencies for some of these electron acceptors are higher than for oxygen, suggesting that these acceptors might be biologically more relevant substrates than oxygen. Recently, putative POX sequences were identified in Actinobacteria with overall sequence identities of 39–24% to fungal POX [13]. A functional POX from Arthrobacter siccitolerans was recombinantly expressed and characterized [13]. POX activity has been also confirmed in the supernatant of the bacterium Pantoea ananatis when cultivated on rice straw [37].

References

- Levasseur A, Drula E, Lombard V, Coutinho PM, and Henrissat B. (2013). Expansion of the enzymatic repertoire of the CAZy database to integrate auxiliary redox enzymes. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6(1):41. DOI:10.1186/1754-6834-6-41 |

- Sützl L, Laurent CVFP, Abrera AT, Schütz G, Ludwig R, and Haltrich D. (2018). Multiplicity of enzymatic functions in the CAZy AA3 family. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(6):2477-2492. DOI:10.1007/s00253-018-8784-0 |

- Ferreira P, Carro J, Serrano A, and Martínez AT. (2015). A survey of genes encoding H2O2-producing GMC oxidoreductases in 10 Polyporales genomes. Mycologia. 2015;107(6):1105-19. DOI:10.3852/15-027 |

- Hernández-Ortega A, Ferreira P, and Martínez AT. (2012). Fungal aryl-alcohol oxidase: a peroxide-producing flavoenzyme involved in lignin degradation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(4):1395-410. DOI:10.1007/s00253-011-3836-8 |

- Daniel G, Volc J, and Kubatova E. (1994). Pyranose Oxidase, a Major Source of H(2)O(2) during Wood Degradation by Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Trametes versicolor, and Oudemansiella mucida. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60(7):2524-32. DOI:10.1128/aem.60.7.2524-2532.1994 |

- Langston JA, Shaghasi T, Abbate E, Xu F, Vlasenko E, and Sweeney MD. (2011). Oxidoreductive cellulose depolymerization by the enzymes cellobiose dehydrogenase and glycoside hydrolase 61. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(19):7007-15. DOI:10.1128/AEM.05815-11 |

- Kracher D, Scheiblbrandner S, Felice AK, Breslmayr E, Preims M, Ludwicka K, Haltrich D, Eijsink VG, and Ludwig R. (2016). Extracellular electron transfer systems fuel cellulose oxidative degradation. Science. 2016;352(6289):1098-101. DOI:10.1126/science.aaf3165 |

- Garajova S, Mathieu Y, Beccia MR, Bennati-Granier C, Biaso F, Fanuel M, Ropartz D, Guigliarelli B, Record E, Rogniaux H, Henrissat B, and Berrin JG. (2016). Single-domain flavoenzymes trigger lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases for oxidative degradation of cellulose. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28276. DOI:10.1038/srep28276 |

- Bissaro B, Røhr ÅK, Müller G, Chylenski P, Skaugen M, Forsberg Z, Horn SJ, Vaaje-Kolstad G, and Eijsink VGH. (2017). Oxidative cleavage of polysaccharides by monocopper enzymes depends on H(2)O(2). Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(10):1123-1128. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.2470 |

- Goswami P, Chinnadayyala SS, Chakraborty M, Kumar AK, and Kakoti A. (2013). An overview on alcohol oxidases and their potential applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(10):4259-75. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-4842-9 |

- Iida K, Cox-Foster DL, Yang X, Ko WY, and Cavener DR. (2007). Expansion and evolution of insect GMC oxidoreductases. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:75. DOI:10.1186/1471-2148-7-75 |

- Sun W, Shen YH, Yang WJ, Cao YF, Xiang ZH, and Zhang Z. (2012). Expansion of the silkworm GMC oxidoreductase genes is associated with immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;42(12):935-45. DOI:10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.09.006 |

-

Mendes S, Banha C, Madeira J, Santos D, Miranda V, Manzanera M, Ventura MR, van Berkel WJH, Martins LO. Characterization of a bacterial pyranose 2-oxidase from Arthrobacter siccitolerans. 2016 J Mol Catal B Enzym 133, S34–S43

-

Westermark U, Eriksson KE. Cellobiose:Quinone Oxidoreductase, a New Wood-degrading Enzyme from White-rot Fungi. 1974 Acta Chem Scand 1974 28b:209–214.

-

Kracher D, Ludwig R. Cellobiose dehydrogenase: An essential enzyme for lignocellulose degradation in nature - A review. 2016 Bodenkultur 67:145–163.

- Hallberg BM, Henriksson G, Pettersson G, Vasella A, and Divne C. (2003). Mechanism of the reductive half-reaction in cellobiose dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(9):7160-6. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M210961200 |

- Phillips CM, Beeson WT, Cate JH, and Marletta MA. (2011). Cellobiose dehydrogenase and a copper-dependent polysaccharide monooxygenase potentiate cellulose degradation by Neurospora crassa. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6(12):1399-406. DOI:10.1021/cb200351y |

- Tan TC, Kracher D, Gandini R, Sygmund C, Kittl R, Haltrich D, Hällberg BM, Ludwig R, and Divne C. (2015). Structural basis for cellobiose dehydrogenase action during oxidative cellulose degradation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7542. DOI:10.1038/ncomms8542 |

- Courtade G, Wimmer R, Røhr ÅK, Preims M, Felice AK, Dimarogona M, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Sørlie M, Sandgren M, Ludwig R, Eijsink VG, and Aachmann FL. (2016). Interactions of a fungal lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase with β-glucan substrates and cellobiose dehydrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(21):5922-7. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1602566113 |

- Bodenheimer AM, O'Dell WB, Oliver RC, Qian S, Stanley CB, and Meilleur F. (2018). Structural investigation of cellobiose dehydrogenase IIA: Insights from small angle scattering into intra- and intermolecular electron transfer mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2018;1862(4):1031-1039. DOI:10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.01.016 |

- Fernández IS, Ruíz-Dueñas FJ, Santillana E, Ferreira P, Martínez MJ, Martínez AT, and Romero A. (2009). Novel structural features in the GMC family of oxidoreductases revealed by the crystal structure of fungal aryl-alcohol oxidase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65(Pt 11):1196-205. DOI:10.1107/S0907444909035860 |

- Mathieu Y, Piumi F, Valli R, Aramburu JC, Ferreira P, Faulds CB, and Record E. (2016). Activities of Secreted Aryl Alcohol Quinone Oxidoreductases from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus Provide Insights into Fungal Degradation of Plant Biomass. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(8):2411-2423. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03761-15 |

- Hecht HJ, Kalisz HM, Hendle J, Schmid RD, and Schomburg D. (1993). Crystal structure of glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger refined at 2.3 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1993;229(1):153-72. DOI:10.1006/jmbi.1993.1015 |

- Yoshida H, Sakai G, Mori K, Kojima K, Kamitori S, and Sode K. (2015). Structural analysis of fungus-derived FAD glucose dehydrogenase. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13498. DOI:10.1038/srep13498 |

- Wong CM, Wong KH, and Chen XD. (2008). Glucose oxidase: natural occurrence, function, properties and industrial applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;78(6):927-38. DOI:10.1007/s00253-008-1407-4 |

- Sygmund C, Klausberger M, Felice AK, and Ludwig R. (2011). Reduction of quinones and phenoxy radicals by extracellular glucose dehydrogenase from Glomerella cingulata suggests a role in plant pathogenicity. Microbiology (Reading). 2011;157(Pt 11):3203-3212. DOI:10.1099/mic.0.051904-0 |

- Volc J, Kubátová E, Daniel G, Sedmera P, and Haltrich D. (2001). Screening of basidiomycete fungi for the quinone-dependent sugar C-2/C-3 oxidoreductase, pyranose dehydrogenase, and properties of the enzyme from Macrolepiota rhacodes. Arch Microbiol. 2001;176(3):178-86. DOI:10.1007/s002030100308 |

- Tan TC, Spadiut O, Wongnate T, Sucharitakul J, Krondorfer I, Sygmund C, Haltrich D, Chaiyen P, Peterbauer CK, and Divne C. (2013). The 1.6 Å crystal structure of pyranose dehydrogenase from Agaricus meleagris rationalizes substrate specificity and reveals a flavin intermediate. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53567. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0053567 |

- Ozimek P, Veenhuis M, and van der Klei IJ. (2005). Alcohol oxidase: a complex peroxisomal, oligomeric flavoprotein. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005;5(11):975-83. DOI:10.1016/j.femsyr.2005.06.005 |

- Koch C, Neumann P, Valerius O, Feussner I, and Ficner R. (2016). Crystal Structure of Alcohol Oxidase from Pichia pastoris. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149846. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0149846 |

- Vonck J, Parcej DN, and Mills DJ. (2016). Structure of Alcohol Oxidase from Pichia pastoris by Cryo-Electron Microscopy. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159476. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0159476 |

- Daniel G, Volc J, Filonova L, Plíhal O, Kubátová E, and Halada P. (2007). Characteristics of Gloeophyllum trabeum alcohol oxidase, an extracellular source of H2O2 in brown rot decay of wood. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(19):6241-53. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00977-07 |

- de Oliveira BV, Teixeira GS, Reis O, Barau JG, Teixeira PJ, do Rio MC, Domingues RR, Meinhardt LW, Paes Leme AF, Rincones J, and Pereira GA. (2012). A potential role for an extracellular methanol oxidase secreted by Moniliophthora perniciosa in Witches' broom disease in cacao. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49(11):922-32. DOI:10.1016/j.fgb.2012.09.001 |

- Hallberg BM, Leitner C, Haltrich D, and Divne C. (2004). Crystal structure of the 270 kDa homotetrameric lignin-degrading enzyme pyranose 2-oxidase. J Mol Biol. 2004;341(3):781-96. DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.033 |

- Leitner C, Volc J, and Haltrich D. (2001). Purification and characterization of pyranose oxidase from the white rot fungus Trametes multicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(8):3636-44. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.8.3636-3644.2001 |

- Sucharitakul J, Prongjit M, Haltrich D, and Chaiyen P. (2008). Detection of a C4a-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate in the reaction of a flavoprotein oxidase. Biochemistry. 2008;47(33):8485-90. DOI:10.1021/bi801039d |

- Ma J, Zhang K, Huang M, Hector SB, Liu B, Tong C, Liu Q, Zeng J, Gao Y, Xu T, Liu Y, Liu X, and Zhu Y. (2016). Involvement of Fenton chemistry in rice straw degradation by the lignocellulolytic bacterium Pantoea ananatis Sd-1. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:211. DOI:10.1186/s13068-016-0623-x |