CAZypedia celebrates the life of Senior Curator Emeritus Harry Gilbert, a true giant in the field, who passed away in September 2025.

CAZypedia needs your help!

We have many unassigned pages in need of Authors and Responsible Curators. See a page that's out-of-date and just needs a touch-up? - You are also welcome to become a CAZypedian. Here's how.

Scientists at all career stages, including students, are welcome to contribute.

Learn more about CAZypedia's misson here and in this article. Totally new to the CAZy classification? Read this first.

Glycoside Hydrolase Family 71

This page has been approved by the Responsible Curator as essentially complete. CAZypedia is a living document, so further improvement of this page is still possible. If you would like to suggest an addition or correction, please contact the page's Responsible Curator directly by e-mail.

| Glycoside Hydrolase Family GH71 | |

| Clan | GH-x |

| Mechanism | inverting |

| Active site residues | known |

| CAZy DB link | |

| https://www.cazy.org/GH71.html | |

Substrate specificities

GH71 comprises enzymes with α-1,3-glucanase activity (EC 3.2.1.59), often referred to as mutanases, based on mutan being an alternative name for α-1,3-glucan (from Streptococcus mutans). Early studies demonstrated that these enzymes hydrolyze pure α-1,3-glucans while remaining inactive toward α-glucans containing mixed α-1,3/α-1,4 linkages [1]. Subsequent work showed that GH71 enzymes act on a broader range of α-1,3-linked glucans, including pseudonigeran and soluble carboxymethylated α-1,3-glucan, but display no activity toward other tested α- or β-linked glycans [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

Depending on the enzyme, GH71 α-1,3-glucanases may exhibit exo- or endo-type hydrolytic activity. Some enzymes with exo activity, such as Agn13.1 from Trichoderma harzianum, showed a 1:1 correlation between glucose released and reducing sugars, typical of exo hydrolysis, and was unable to cleave periodate-oxidized S-glucan, which is resistant to exo-α-1,3-glucanases [5]. Endo-acting GH71 enzymes include Agn1p from Schizosaccharomyces pombe which does not hydrolyze pNP-α-glucose, and is not inhibited by classical exo-glycosidase inhibitors such as 1-deoxynojirimycin, castanospermine, or D-glucono-1,5-lactone [6]. MutAp from T. harzianum, an endo-hydrolytic α-1,3-glucanase, is suggested to act processively from the non-reducing end, repeatedly releasing glucose before dissociating [8, 9]. Its insensitivity to multiple exo-glycosidase inhibitors, and experiments with reduced oligosaccharides (e.g., G5-ol) further yield no products compatible with exo activity (e.g., G4-ol). The minimum chain-length requirement for MutAp has been shown to be a tetrasaccharide.

The Aspergillus nidulans enzymes AnGH71B and AnGH71C display distinct behaviors when acting on reduced oligosaccharides (nigeropentaose and nigerohexaose), reflecting different cleavage mechanisms [7]. AnGH71C exhibits a pattern consistent with endo-cleavage, evidenced by the diverse products generated from reduced nigerohexaose. In contrast, AnGH71B displays exo-processive characteristics despite the absence of released reduced glucose, explained by the inability of subsite +1 to accommodate the reduced unit and therefore preventing classical terminal cleavage.

Overall, GH71 enzymes exhibit strict specificity for continuous regions of α-1,3-glycosidic linkages, with no tolerance for alternating segments containing α-1,4 linkages [1, 5], as found in the polysaccharide nigeran (α-1,3/1,4-glucan). End products range from glucose (e.g. from endo-acting processive action), to nigerooligosaccharides with DP 2–7 [4, 6, 9]. Nigerotriose has been found as a final product together with glucose from endo-acting processive GH71 enzymes [7, 8].

Kinetics and Mechanism

The anomeric configuration of the products released by α-1,3-glucanases has been elucidated by complementary NMR and crystallography approaches. In the case of MutAp from T. harzianum, the hydrolysis of carboxymethylated α-1,3-glucan was monitored by ¹H NMR, revealing the appearance of β-Glc signals and the complete absence of α-Glc, demonstrating inversion of the anomeric configuration [8]. NMR studies of AnGH71B and AnGH71C from A. nidulans likewise showed inversion of products, and structures including the inverted anomer of the product nigerose further supports these findings [7].

Catalytic Residues

Three conserved acidic residues (Asp69, Asp237, and Glu240) were identified in the active site of Agn1p by Horaguchi et al. [10]. Individual substitutions of these residues (D69N, D237A/N, E240A/Q) led to drastic reductions in activity on α-1,3-glucan.

Structure-guided mutational studies of AnGH71B and AnGH71C directly identified the catalytic residues Asp265 (general base) and Glu268 (general acid), functionally separating subsites −4 to +3 of the enzymes [7]. The simultaneous observation of the α-linked substrate nigerotetraose and β-anomer of nigerotriose as product in the active site, together with an arrangement of a water molecule positioned ~3.2 Å from the anomeric carbon of the substrate, supported a classic inverting mechanism, in which Asp265 activates the nucleophilic water and Glu268 protonates the leaving group. Substitution of these residues resulted in 200- to 15,000-fold reductions in activity, confirming their catalytic role.

Three-dimensional structures

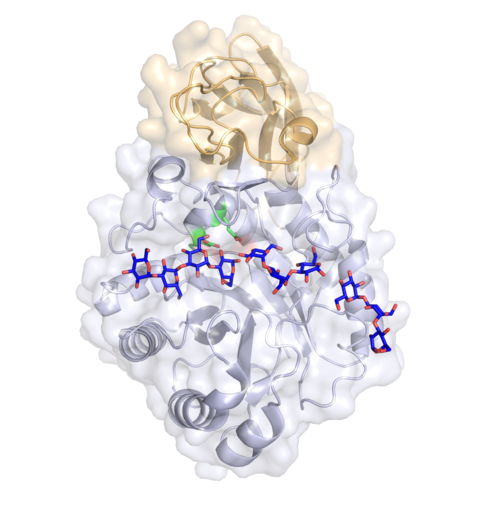

The three-dimensional structure of GH71 enzymes has been elucidated through two independent crystallographic studies, both revealing that members of this family adopt a classic (β/α)₈ TIM-barrel core, closely associated with a C-terminal β-sandwich accessory domain [7, 10].

The first structural description, obtained for S. pombe Agn1p, showed that its TIM barrel forms a deep cavity accessible to the solvent, consistent with the catalytic cleft observed in other glycoside hydrolases. Structural work on A. nidulans AnGH71C corroborated this overall fold and showed that the β-sandwich closely resembles an Ig-like fibronectin III domain, compacting closely against the TIM barrel to form a long substrate-binding cleft comprising at least seven subsites (−4 to +3). The structures of ligand complexes revealed minimal protein rearrangement upon binding but highlighted a conformational packing of the β6–α6 loop over subsites +1 to +3, contributing to substrate stabilization.

Simulations and geometries of the bound state further indicated that GH71 enzymes exploit the intrinsic low-energy conformations of α-1,3-linked oligosaccharides, while a high-energy configuration around the −1/+1 region likely prepares the glycosidic bond for cleavage.

Family Firsts

- First stereochemistry determination

- The stereochemistry of GH71 enzymes has been resolved by monitoring the anomeric configuration of the released glucose using ¹H NMR spectroscopy, confirming that the enzymes operate through the inversion mechanism [8].

- First general acid/base residue identification

- In AnGH71C, the catalytic residues have been identified as a dyad, with an aspartate residue (Asp265) acting as a general base that activates the catalytic water molecule, and a glutamate residue (Glu268) acting as a general acid that protonates the leaving group [7].

- First 3-D structure

- The first solved structure of a GH71 enzyme was of Agn1p from S. pombe, published in June 2025 by Horaguchi et al. [10], which demonstrated that members of the GH71 family possess a classic (β/α)₈ TIM-barrel core closely associated with a C-terminal β-sandwich accessory domain. In August the same year, Mazurkewich et al. published the structure of AnGH71C from A. nidulans, which additionally included structures with glucose and nigerooligosaccharides bound in the active site, respectively [7].

References

- Zonneveld BJ (1972). A new type of enzyme, and exo-splitting -1,3 glucanase from non-induced cultures of Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;258(2):541-7. DOI:10.1016/0005-2744(72)90245-8 |

-

Imai K, Kobayashi M, Matsuda K. (1977). Properties of an α-1,3-glucanase from Streptomyces sp. KI-8. Agric Biol Chem. 1977;41(10);1889-95. DOI: 10.1080/00021369.1977.10862782

- Fuglsang CC, Berka RM, Wahleithner JA, Kauppinen S, Shuster JR, Rasmussen G, Halkier T, Dalboge H, and Henrissat B. (2000). Biochemical analysis of recombinant fungal mutanases. A new family of alpha1,3-glucanases with novel carbohydrate-binding domains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(3):2009-18. DOI:10.1074/jbc.275.3.2009 |

- Villalobos-Duno H, San-Blas G, Paulinkevicius M, Sánchez-Martín Y, and Nino-Vega G. (2013). Biochemical characterization of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis α-1,3-glucanase Agn1p, and its functionality by heterologous Expression in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66853. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0066853 |

- Ait-Lahsen H, Soler A, Rey M, de La Cruz J, Monte E, and Llobell A. (2001). An antifungal exo-alpha-1,3-glucanase (AGN13.1) from the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma harzianum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(12):5833-9. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.12.5833-5839.2001 |

- Dekker N, Speijer D, Grün CH, van den Berg M, de Haan A, and Hochstenbach F. (2004). Role of the alpha-glucanase Agn1p in fission-yeast cell separation. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(8):3903-14. DOI:10.1091/mbc.e04-04-0319 |

- Mazurkewich S, Widén T, Karlsson H, Evenäs L, Ramamohan P, Wohlert J, Brändén G, and Larsbrink J. (2025). Structural and biochemical basis for activity of Aspergillus nidulans α-1,3-glucanases from glycoside hydrolase family 71. Commun Biol. 2025;8(1):1298. DOI:10.1038/s42003-025-08696-3 |

- Grün CH, Dekker N, Nieuwland AA, Klis FM, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JF, and Hochstenbach F. (2006). Mechanism of action of the endo-(1-->3)-alpha-glucanase MutAp from the mycoparasitic fungus Trichoderma harzianum. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(16):3780-6. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.062 |

- Sinitsyna OA, Volkov PV, Zorov IN, Rozhkova AM, Emshanov OV, Romanova YM, Komarova BS, Novikova NS, Nifantiev NE, and Sinitsyn AP. (2025). Physico-chemical properties and substrate specificity of α-(1→3)-d-glucan degrading recombinant mutanase from Trichoderma harzianum expressed in Penicillium verruculosum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2025;91(2):e0022624. DOI:10.1128/aem.00226-24 |

- Horaguchi Y, Saitoh H, Konno H, Makabe K, and Yano S. (2025). Crystal structure of GH71 α-1,3-glucanase Agn1p from Schizosaccharomyces pombe: an enzyme regulating cell division in fission yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2025;766:151907. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2025.151907 |